Front Squat to Replace Back Squat Due to Bad Knees

Knee pain during squats is a very common complaint of lifters, leading many to stop this exercise all together. Fortunately, by optimizing and modifying your form and programming, you can overcome this barrier and return to squatting without knee pain!

What Symptoms Should I Look Out For?

The following recommendations are for those who've had what I like to call "cranky" knees. This is not for an acute traumatic injury such as a recent ACL tear, bone bruise, or patellar dislocation. If that sounds like you, you should go through formal physiotherapy first in order to return to baseline, prior to implementing the strategies here.

Additionally, symptoms such as unexplained swelling, locking, buckling, or falling would also warrant medical attention first prior to trying the recommendations listed below.

What Type of Knee Pain Do You Have?

If you're dealing with knee arthritis, patellofemoral pain syndrome, a degenerative meniscus tear, or quadriceps/patellar tendinopathy, you're in luck. While all of these diagnoses are different, the solution to overcoming knee pain with squats is relatively the same, and it all boils down to this:

Temporarily reduce load on the knee, force an adaptation to occur, and then gradually build your tolerance back up.

First…Do You Have the ROM?

One of the first things you should look at if you have knee pain during squats, is if you have the required range of motion in the knee to perform the lift. Generally speaking, in a low bar back squat performed to "depth" defined as the greater trochanter of the hip being lower than the top of the kneecap, the knee will bend to about 120° of flexion.

For those who are performing front squats or overhead squats where the depth is increased, it can require much more knee flexion, and even end range for exercises such as the clean or snatch. In order to test knee range of motion, you can lie down and pull your heel up to your butt and see if it causes pain or tightness.

If you experience pain towards the end range of motion, you'd want to make sure you're not performing a variation that requires the motion that you don't currently have.

If you find that you have a painful knee flexion limitation, you can work on slowly restoring this with an exercise called heel slides. Perform 10-15 reps with a 5 second hold. If you continue to have a ROM deficit, a consultation with a physiotherapist may be warranted.

Ensure Efficient Knee Tracking

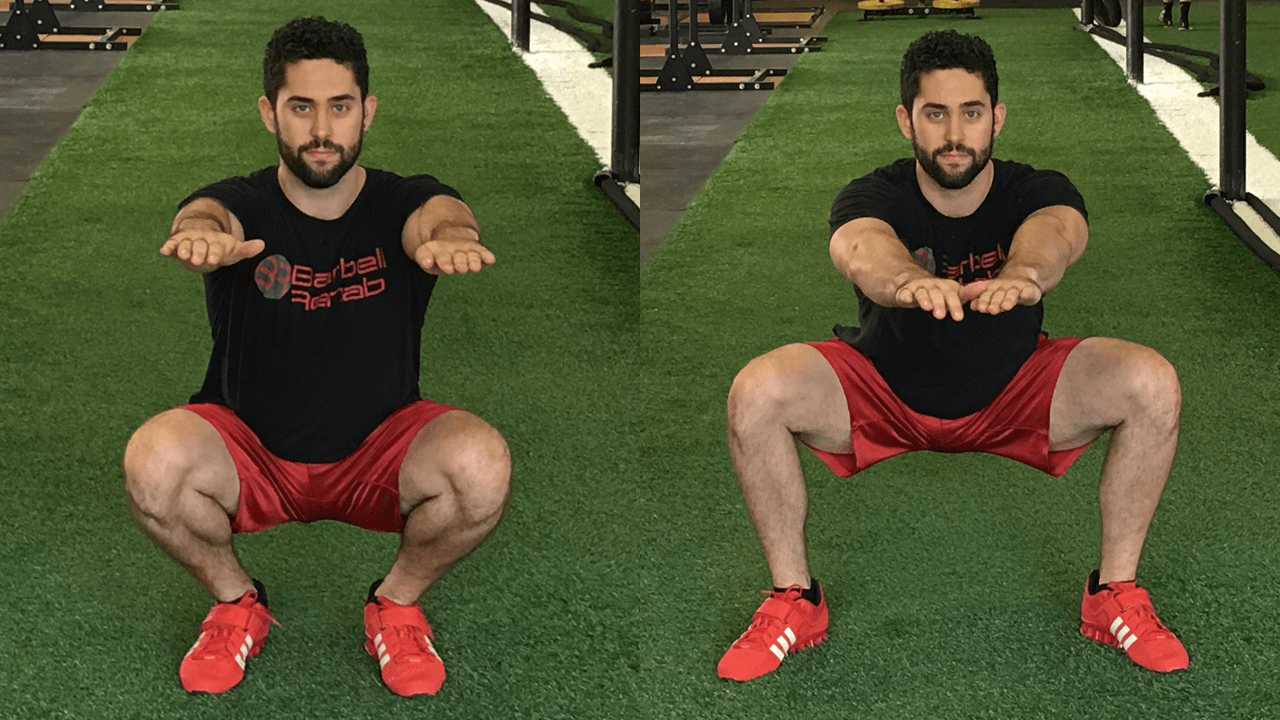

Now that you've determined that you have enough knee range of motion to perform the squat variation of your choice, you should make sure your knee is tracking optimally with both the joint above (the hip) and below (the ankle).

While allowing for some knee valgus (knees inward) is probably nothing to be too concerned about, as long as it's controlled and loaded appropriately, you still want to try your best to get your knees out over your feet. This will also ensure that your hips are abducted to be in line with the knees.

When we squat with the hips in an abducted position, this puts the hip adductor musculature in an optimal length-tension relationship to contribute to hip extension!

This hip position is less stress on the knee because it utilizesMORE MUSCLE MASS. By utilizing this position, many with knee pain during squats will begin to feel it in their adductors vs. the anterior knee.

Optimize the Programming and Dosage

Now that you've optimized your knee position, let's make sure you're programming the squat effectively. Why? Because it wouldn't make sense to change any other variables including the form or exercise itself, if you're not applying the optimal dose.

Regardless of what squat variation you're using, the majority of your working sets should be performed at a rate of perceived exertion or RPE of 7-8.5. This equates to an actual intensity of around 80-85% one-rep max.

If you're having knee pain from squats, and you're consistently training them to failure, no amount of foam rolling, mobility work, or form modifications is going to help. This is a programming error! So the first thing I'd do if you're dealing with knee pain with squats, is reduce the intensity a bit. Sometimes this is all you need in order to squat without knee pain.

Modify Your Stance Width and Degree of Toe Out

Stance width and degree of toe-out can also be optimized for those who suffer from knee pain during squats. Generally speaking, gravitating towards a wider stance with a larger degree of toe-out (20-30°) tends to be more tolerable in this case.

A wider stance makes the squat more of a hip dominant movement, thus taking stress off of the knees. Additionally, turning the toes out sets the knee up for optimal alignment, limiting the amount of tibial internal/external rotation occurring at the knee.

Choose the Optimal Bar Position

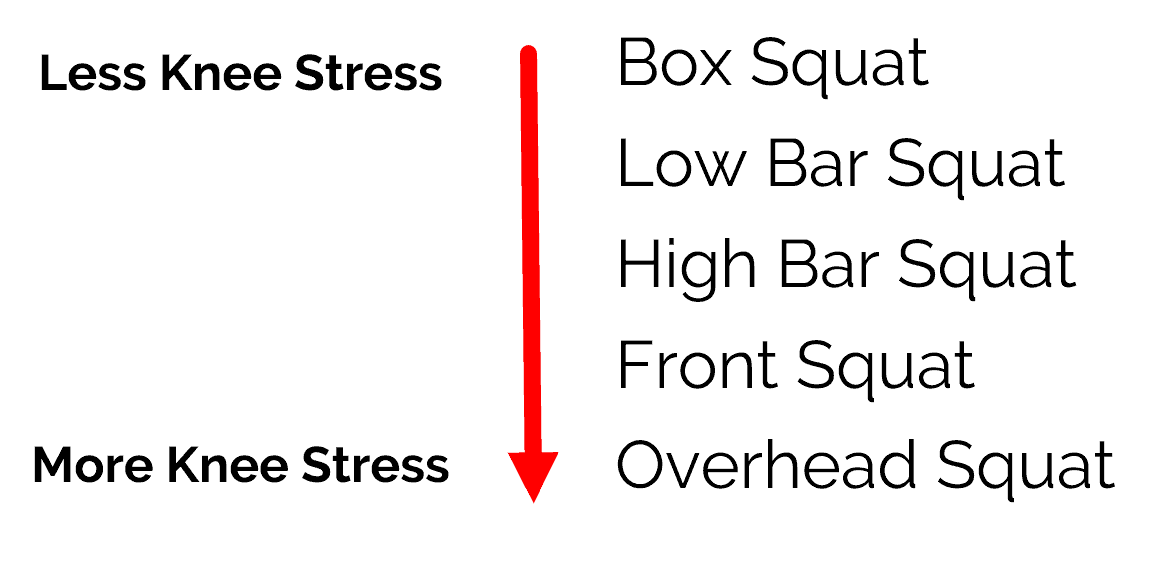

If you widened the stance a bit and turned your toes out and are still dealing with knee pain during squats, you may want to change your bar position next. Due to the varying amounts of forward knee translation, different squat variations place different amounts of stress on the knee.

In general, overhead and front squats will be the most stress on the knee, and box squats and low bar squats will be the least.

This doesn't mean that overhead and front squats are necessary "bad" for the knee, but if you're currently dealing with knee pain AND you're performing an overhead or front squat, it may be best to temporarily switch to another variation to allow the knee to calm down.

For example, if you have knee pain with front squats, try switching to a low bar squat for 4-6 weeks to allow the knee to calm down. Once you're feeling better, gradually introduce the front squat and build up your tolerance to it again.

What About High Bar vs. Low Bar?

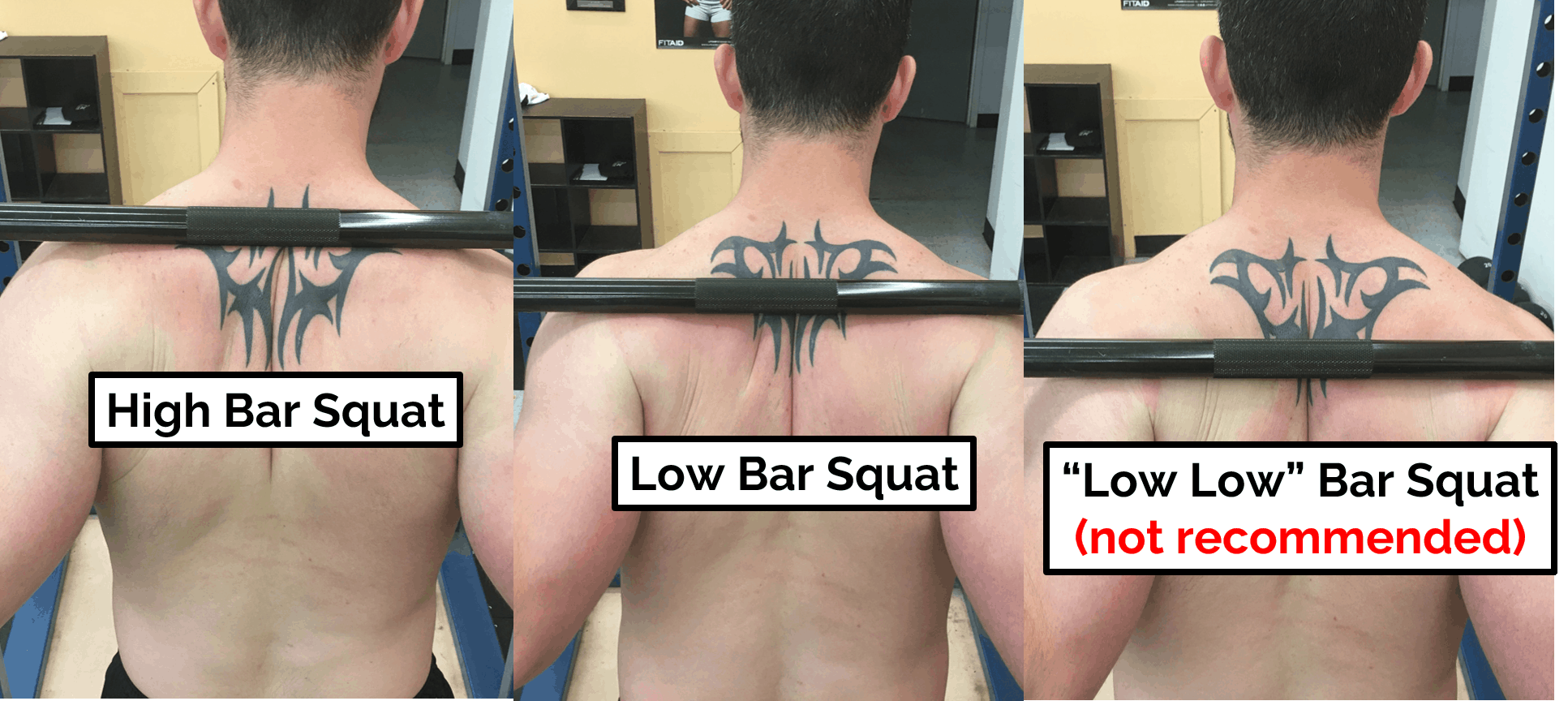

When it comes to the back squat, we have essentially two choices: the high-bar or low-bar position.

With the high-bar position, the bar is held on a muscular shelf created by contraction of the upper trapezius muscles. This creates a squat characterized by a more upright torso and decreased hip flexion but INCREASED forward migration of the knee.

As I mentioned before, while there is nothing inherently wrong with forward knee migration, (it's actually necessary for the high-bar squat) for those who struggle with knee pain during the squat, it would be best to temporarily choose a variation that limits this. Again, the idea here isPAIN-FREEsquatting!

With the low-bar position, the bar is carried further down the back, on a muscular shelf created by the rear deltoids. This promotes a squat with more forward torso lean, more hip flexion, butLESS forward migration of the knee. Due to less forward knee migration and heavy posterior chain recruitment, this variation tends to be optimal for those who suffer from knee pain with squats.

Tempo Squats for Knee Pain

A great way to help reduce symptoms and improve knee tolerance is to implement tempo squats into the program. If you are dealing with a quadriceps/patellar tendinopathy, or have symptoms of osteoarthritis, slowing down the movement can help create the permanent positive structural changes you are looking for.

To perform tempo squats, you're going to have to reduce the load a good bit, since the entire movement will be slower. I recommend using a 3:0:3 tempo here. This means you're going to slowly squat down for 3 seconds, and then stand up for 3 seconds too. Here's a video of what I'm looking for.

You can run these for 4-6 weeks, or as long as you need to in order for the symptoms to calm down.

A Note on Meniscus Tears

Should you squat with a meniscus tear? The answer is...it depends. It depends if there was an actual acute injury, meaning there was a distinct, recent point in time where you cut and pivoted, fell, and injured it in a sport. This is usually associated with an immediate decrease in motion and swelling. If this sounds like you, then you should seek a medical consult.

However, if you've never suffered an actual "injury" and aren't experiencing symptoms such as buckling and locking and you discover than you have a meniscus tear on MRI, exercise is the best option for you. In fact, in one study, 43% of athletes that had NO knee pain showed some sort of meniscus pathology on MRI.

This goes to show you that meniscus tears and damage doesn't always correlate with pain. For these "degenerative" tears, a.k.a. those that just slowly happen over time with age, exercise (which includes squats) is the first line of defense. Find a load and variation this is tolerable, and slowly progress from there.

What to Do If None of this Works

Sometimes no amount of programming and form optimization and modification will help reduce your knee pain during squats. If this is the case, you may want to take a complete break from the squatting pattern all together for 4-6 weeks.

This will allow the squat patter to completely desensitize, and in the meantime you can increase the volume on posterior chain dominant exercises like the deadlift. A good example of a "squat-less" posterior chain dominant lower body day may look like this (with video links):

- Deadlift 4 x 3

- Barbell Hip Thrust 3 x 8

- DB RDL 3 x 12

- Barbell Torque 3 x 8 / side

- RKC Plank 4 x 15" hold

If you're knee is really flared up, and you can't tolerate any squatting patterns, run the workout above for 4-6 weeks and then gradually reintroduce the squat back into the program as you can tolerate it.

Putting it All Together

Knee pain during squats can be an annoying injury to work around, especially if you're not managing it optimally. Fortunately, with the tips provided above, you should be squatting pain free in no time! Remember, in general:

- Ensure you have enough knee ROM for the squat variation of your choice. Use the knee joint clearing test to verify this

- Make sure your knee is tracking over your toe, and avoid excessive varus or valgus stresses

- Optimize the programming by avoiding too much training volume above an RPE 8.5 or 85%.

- Temporarily change to a low bar or box squat to reduce forward knee translation and limit stress on the knee

- Try slowing down the movement with tempo squats to force an adaptation if dealing with a tendinopathy

- Temporarily remove the squat all together if none of this works, and train posterior chain only movements for a while.

Implement the changes above to rid your knee pain during squats once and for all!

Front Squat to Replace Back Squat Due to Bad Knees

Source: https://barbellrehab.com/squat-without-knee-pain/

0 Response to "Front Squat to Replace Back Squat Due to Bad Knees"

Post a Comment